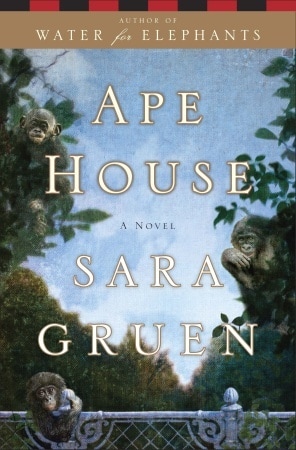

Written by Lauryn Smith Undeterred after reading Sara Gruen’s unassuming “At the Water’s Edge,” I took up “Ape House.” Now that I am done reading it, I wonder if Gruen might be a one-hit wonder. (Don’t get me wrong. Her writing style is lovely. “Water for Elephants” is, and probably always will be, one of my favorite books.) As much as I hate to say it, “Ape House” left me dizzy, and not in a good way. “Ape House” is a contemporary dual-track story that begins well enough. Readers are introduced to John Thigpen, a journalist in Philadelphia who is writing a story on the six bonobos at the Great Ape Language Lab in Kansas. These particular apes are remarkable because they can use American Sign Language and computer software to reason, communicate and form deep relationships. John travels to meets the apes and lab staff, including Isabel Duncan, a scientist who regards the bonobos as family. On the night of the interview, Isabel and the apes are the victims of an explosion at the lab. The apes escape unharmed but are whisked away by an unknown force to an unknown location. Isabel, on the other hand, is tragically injured. During her long recovery, she makes it her goal to retrieve the apes to ensure their welfare. With the help of a disjointed ensemble, Isabel discovers that the apes were sold to Ken Faulks, a renowned pornographer. Yep, you read that right. This point, barely halfway into the book, is when the story becomes irritating. Gruen chooses to satirize human life by placing the bonobos in the hands of an adult film connoisseur, who in turn places the apes in a house full of cameras that broadcast live in the name of entertainment, considered such because of the bonobos’ inherent sexual inclinations. Gruen seems to struggle with the directionality of the story. Clearly, “Ape House” is fiction, but its content is based largely on Gruen’s real-life experiences at the Great Ape Trust in Iowa, where she conducted much of her research for the book. In fact, many of the ape encounters she describes are ones she experienced firsthand, such as the establishment of goodwill with the apes through the presentation of backpacks full of goodies, an act John mirrors in the beginning of the novel. The book would have been sincerer, and would have avoided many of its flaws, which we will discuss momentarily, if Gruen had chosen the direction of nonfiction. With the best of the book’s content being inspired by fact, the transition would not have been an unreasonable one.

Instead, Gruen sprinkles in endearing, fictionalized anecdotes based on real bonobo encounters, then encumbers them with the fluff that composes the rest of the novel. It often seems as though she could not decide on the type of story she wanted to tell. She throws in elements of simian research, animal cruelty, potential infidelity, paternal uncertainty, even drugs and booze. She oscillates between all these elements and more, some getting more attention than others, but no one receiving the attention needed to be deeply meaningful to the story overall. In fact, most do nothing more than act as half-baked, dead-ended shock factors, and, unfortunately, they come off as disingenuous. And, although written as to appear true-to-life, there is a lacking sense of authenticity. The details Gruen incorporates are reaching. For instance, would a reality show about a houseful of apes lounging around, ordering junk food and having periodic sexual encounters truly be all that popular? Maybe? Gruen relies heavily on clichés, not only in plot development, but also in characterization. Isabel, for instance, does not easily form relationships with people, not even her own family. Add to that the fact that her ex-boyfriend, who headed the destroyed lab, turns out to be a sleazeball who has a sketchy past and plays a significant role in the bonobos’ current predicament. Naturally, Isabel is protective of the bonobos, who in turn have eyes only for her, and she is suspicious of nearly everyone. These characters are predictable and vanilla yet vital to the story. Want another example of cliché characterization? Let’s talk about Cat, the overzealous reporter John works with, the one who snags unapproved photos of Isabel while she is still recovering in the hospital and who steals the ape story from John, ultimately catalyzing his departure from the Philadelphia Inquirer. Who could have seen that coming? John’s unbearable in-laws, spunky interns, vegan animal rights activists, Russian strippers… You get the picture. Formulaic, right? We did not even touch on the varied, commonly used plot points, which range from baby talk to bar punches to a meth lab explosion. Now that some of the book’s banalities are established, let’s turn to some other shortcomings. For one, the conflicts Gruen portrays are too conveniently resolved. The apparent struggles pose little imposition. (See: friendly computer hackers saving the day.) What is more, the book is busy. It is jam-packed with a hodge-podge of scenes that are stitched together coherently but not quite appealingly. For being so full of stuff, the book misses out on a deeper focus on the bonobos, who are arguably the best part of the story. In place of heightened familiarity with the apes, we are forced to grow acquainted with the main humanoid characters of John and Isabel, neither of whom are all that charming. We coast through some brief highs and lows, and then we arrive at an unsurprising, life-is-amazing, everyone-is-pals ending. Do not let my gripes deter you from reading this book. Gruen is a good storyteller, despite missing the mark with parts of this novel’s construction. Her effortless writing still shines. Though the balance of elements is slightly jarring, her organization is on point. Besides, it is always a pleasure to read an author who demonstrates passion for the subject written about, as Gruen does. She details one of humans’ closest living relatives and the fascinating feat of interspecies communication, which is always mind-bending. In effect, she produces a work that advocates against the poor treatment of animals, particularly in entertainment and research. She attempts to elucidate human cruelty and ignorance, and she encourages compassion. Honestly, there is no easy way to detail “Ape House.” I am sure I am not the only one who finds its simple, concise synopsis misleading. If you are hoping for a literature-like read, as I was, “Ape House” is not for you. Gruen would have benefited from narrowing her focus—what might have been impactful in nonfiction form comes off as superficial, predictable and a bit unoriginal in this fiction. That said, the book is a fast read, one that is not conducive to the moral ponderings its context admittedly deserves, which is not necessarily a bad thing, particularly if you are looking for a light weekend read. I suggest checking out some bonobo pics if you choose to read “Ape House.” You know, to immerse yourself in the subject matter. Title: Ape House Author: Sara Gruen Publisher: Spiegel & Grau Publication date: September 2, 2010 Page count: 320 List price: $26 ISBN: 978-0385523219

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Enjoying my book reviews? If you’ve found them helpful or simply love diving into a good book, consider supporting my caffeine-fueled reading sessions! Your contribution helps keep the reviews coming and ensures I stay wide awake for those late-night reading marathons. Cheers to a shared love for literature! ☕️

Categories

All

|